A mountain of clothes looms up some ten metres high as you enter the exhibition space of

Power Station of Art. Act of intimidation? Remnants of past visitors who didn’t meet the dress code?

The imposing installation was first shown at Paris’ Grand Palais in 2010. Above the giant pile of clothes, the claw of a mechanical crane periodically descends, picking up a few garments. ‘Why is the claw grabbing some of the items, and leaving others? Why is it that, at my age, some people are dead already while I’m still alive?’ asks the 74-year-old artist Christian Boltanski.

Do not listen to people who say that Boltanski has a fascination with death. In fact all he talks about is life, and what lives on of us after we pass away. The man himself isn’t as grave as his work would suggest. ‘I’m a very cheerful person,’ he says. ‘I come to terms with my problems by talking about the problems of others.’

Boltanski was born in Paris, in 1944, just two weeks after the city was liberated from the Nazis. His Jewish father had been in hiding for months under the floorboards of the family apartment. When he began making art in the late ’50s, he would recall stories from his childhood, memories haunted by a Holocaust never to be seen, but implicitly present. Today, the child born after the war has grown into a poised, soft-spoken man. Mildly aloof, even. Unimpressed by his own status as one of the most influential figures in the art world.

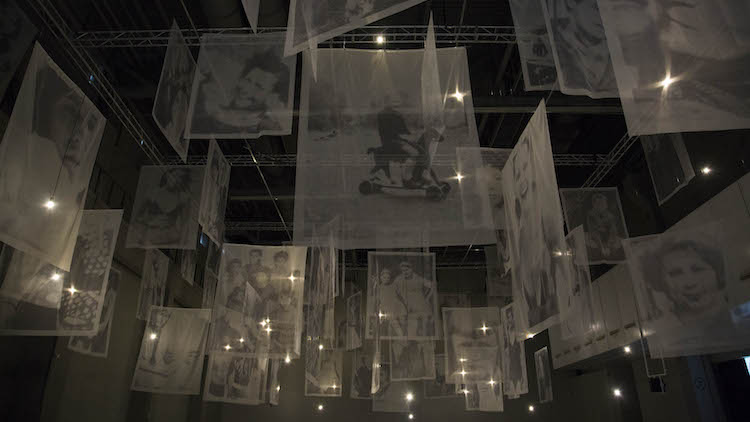

Storage Memory, his current retrospective, gives a good overview of his prolific career. Discarded clothes, old photographs, light bulbs shining like candles on altars: his signature is instantly recognisable. His installations – massive in scale, relatively simple in their conception – are very compelling and, like the man himself, open to speculation. ‘I ask questions,’ he says, ‘but I don’t have any answers. Generally I don’t like people who think they have any answers. Those people are dangerous.’

His questions go unanswered, then, and remain all the more pressing. What’s a human life? Can you symbolise it? Preserve its essence? Can you even digitise it? After all, internet and social media can also be said to serve as a collective ‘storage memory’. ‘Absolutely, I’m very interested in computers...I’ve been thinking about doing a project on Facebook. It’s funny with Facebook, how people are kept there forever. I have people requesting me as friends, while I know they’ve been dead for years.’

As to how to approach his exhibition, Boltanski explains, ‘It’s a path, that's what I call it. The visitor needs to walk through it, be immersed in it… I'd like people to withdraw into themselves when they come to see the show, like when you walk into a temple or a church in a foreign country and you don't understand exactly what's happening. But you know something is happening.’

Michel de Montaigne wrote that ‘to philosophise is to learn how to die.’ Boltanski seems to have applied this motto to his art. And so we walk his path, dutiful visitors learning how to die. But rest assured, it's a gentle and metaphysical death. A death you can enjoy dying.